Get Ready for a Better Search Experience with Microsoft's ChatGPT Integration?

Microsoft's ChatGPT-Bing integration solves data problems, but the real challenge is designing an interface that knows when to give one answer vs. many.

This post was written in 2023. Some details may have changed since then.

This week, some news outlets reported that Microsoft is working to incorporate ChatGPT features into Bing Search. Since I wrote about "will chatGPT replace Google?" in the past, I want to provide additional thoughts here.

Indexing web content is no longer a barrier.

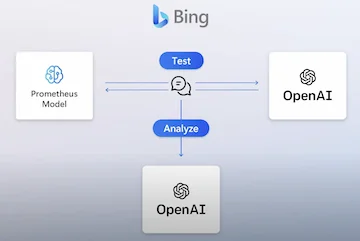

Microsoft reportedly invested $1 billion into OpenAI back in 2019. So it means the partnership between the two companies has been ongoing for at least three years. Bing Search can obviously index the web, so we have to assume that web content indexing is not an issue if OpenAI wants to expand the chatGPT dataset beyond 2021. Given the scale of Microsoft, we can assume that its realtime indexing/crawling capability should be quite good too vs. Google's.

Bing already has image, video content, etc... as part of its dataset so again this won't be a barrier for OpenAI's chatGPT.

Bing Search can rank content trustworthiness relatively well

While I haven't looked at the most recent comparison between Google Search and Bing Search results, it is safe to say that the gap between the two companies' capability in determining the trustworthiness of a piece of content should not be too large. So again, with Microsoft's help, finding the most accurate answer may not be a big barrier for OpenAI/chatGPT.

One specific example is that chatGPT doesn't have updated service rating data, so it can not answer questions about local services like "best plumber near me" or "best Chinese restaurant near me." This is where the Microsoft dataset comes in to help.

A user interface problem

While there is a valid argument to be made about how user-friendly ChatGPT experience is, it is not the one size fit experience for all questions/queries. In many instances, users want to have multiple answers. For example, with the same local service above, users often want to see a list of suitable choices. One can argue that in those cases, users then need to modify the prompt for ChatGPT to be "give me 5 choices of the best xyz service near me" vs. "the best xyz service near me."

I would argue, however, that doing this is not enough though. The search engine should be intelligent enough to know that in many instances, there is no single best answer or a short list of best answers. The best answer is situation-dependent/context-dependent.

In addition, we have facts and we have opinions. They are entirely different from each other.

So how to design an user interface that can be best for multiple scenarios is key. For example, even for something as simple as "recipe for Vietnamese baguette" :D, this is what I get from Google, Bing and ChatGPT as of Jan 2023. It is not obvious which one is better or chatGPT answer is better.

The key then is to dynamically change the search result interface based on user intent, using machine learning. I am not sure how easy or difficult it is to do this. But it seems like a logical step to combine the strength of the single answer style from ChatGPT and a Search engine.

A language assistant

I would argue that providing answers from a pure information search perspective is not why people like ChatGPT, it is the ability to give chatGPT context and then ask it to complete a language-related task like writing a poem, an introduction, an essay, etc...

This use case is very different from a search engine and more closely related to the ability to generate PowerPoint narratives or write in Microsoft Word. So I actually think that the news about Microsoft incorporating different OpenAI capabilities into Office 365 suite is a better news.

The limits of language

Jacob Browning and Yann Lecun wrote an excellent article about AI and the limits of language back in Aug 2022, before ChatGPT was opened to the public. While their article referenced LaMDA, the content is essentially applicable to chatGPT too or any other Large language model. The article is long so if you want to have the key points, here they are:

A Google engineer recently declared Google's AI chatbot, LaMDA, a person, leading to a variety of reactions. The chatbot, LaMDA, is a large language model (LLM) that is designed to predict the likely next words to whatever lines of text it is given.

Some people scoffed at the idea, while others suggested that the next AI might be a person. The diversity of reactions highlights a deeper problem: as these LLMs become more common and powerful, there is less agreement over how to understand them. The underlying problem is the limited nature of language. It is clear that these systems are doomed to a shallow understanding that will never approximate the full-bodied thinking we see in humans. This is because language is only a specific, limited kind of knowledge representation. It excels at expressing discrete objects and properties and the relationships between them, but struggles to represent more concrete information, such as describing irregular shapes or the motion of objects. There are other representational schemes, such as iconic knowledge and distributed knowledge, which can express this information in an accessible way.

Language is a low-bandwidth method for transmitting information, and is often ambiguous due to homonyms and pronouns. Humans don't need a perfect vehicle for communication because we share a nonlinguistic understanding. Large Language models (LLMs) are trained to pick up on the background knowledge for each sentence, looking to the surrounding words and sentences to piece together what is going on. LLMs have acquired a shallow understanding of language, but this understanding is limited and does not include the know-how for more complex conversations. As a result, it is easy to trick them by being inconsistent or changing languages. LLMs lack the understanding necessary for developing a coherent view of the world.

While language can convey a lot of information in a small format, much of human knowledge is nonlinguistic and can be conveyed through other means such as diagrams, maps, artifacts, and social customs. It suggests that a machine trained on language alone will not be able to fully approximate human intelligence because it only has access to a small part of human knowledge through a narrow bottleneck and that the deep nonlinguistic understanding of the world is necessary for language to be useful. It also implies that there are limits to how smart machines can be if trained solely on language.

That's from me. What do you think? Do you see yourself switching from Google to a ChatGPT-powered Bing, or does habit keep you on Google? :)

Cheers,

Chandler